EU for EUquality

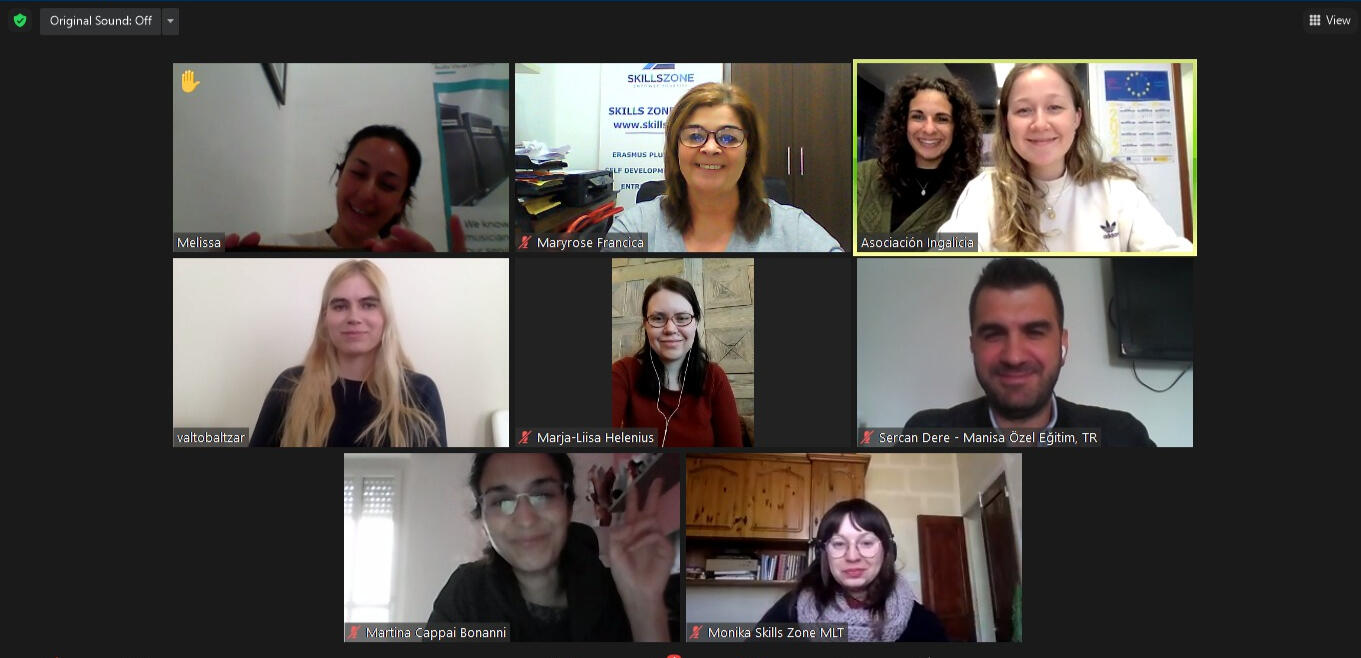

EUqualizer is an Erasmus+ project run by 5 countries (Spain, Malta, Finland, Turkey and Italy) in which we will tackle the problem of stereotypes. The project was created with a purpose to target educational institutions and organisations and help them bring conversation about stereotypes to different learning environments. In our project we will focus on 4 groups that need our attention: LGBT+ community, gender inequality, disability and racism.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

ABOUT

EUqualizer is a project that is a result of an international collaboration of 5 organisations from Spain, Italy, Turkey, Malta & Finland.The objectives of the project are based on the context and data which shows that many people daily experience daily unequal opportunities, injustices, hate speech and are overall put aside in the policy making level as well as when integrating in the society.Through different activities, such as creation of a research, awareness campaign and a creation of toolkit, we want to shine a light on all the injustices happening and also equip different organisations, schools with a toolkit, they can implement in their daily activities.We want to raise attention, we want to start a conversation and we want to make a change!

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This web page and all its content reflects the views only of the author and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

PARTNERSHIP

INGALICIA

Ingalicia is an NGO from A Coruña, Spain, that works on the field of youth, organising events, project and local initiatives to encourage a youth participation in the civic society and democratic life. They are a part of the Eurodesk network, informing young people of European opportunities.

ARCIGAY

Arcigay Torino “Ottavio Mai” is a local committee of Arcigay, one of the main LGBTQIA+ NGOs in Italy. Based in Turin, Arcigay Torino is a volunteer-based association whose mission is the dismantling of all prejudice and discrimination still faced by the LGBTQIA+ community, always keeping an intersectional approach. Our main focus includes education, advocacy, health, emotional and social support.

LEARNING FOR INTEGRATION RY

The mission of Learning for Integration ry, founded in 2012, is to promote the learning of languages and cultural sensitivity of migrant, immigrant and refugee children and youth in Finland and other Nordic countries in order to facilitate their integration into the new culture and the development of a multicultural society. We have a solid background in language teaching and material creation and we would like to use this experience to support our mission to create language awareness through activities such as playgroups for pre-school children, language exchange groups for adults and free language learning material and eLearning possibilities for all ages. We also participate in several Erasmus+ and NordPlus projects regarding immigration and language learning, technology and media, social issues, entrepreneurship, disadvantaged groups etc.

SKILLS ZONE

Skills Zone Malta is a training hub of 20 professional trainers in the field of Entrepreneurship, personal development and soft skills, training people in both f2f and online environment. Our area of expertise is in Entrepreneurship, Social Inclusion, Conflict Resolution, Wellbeing, Communication Skills, Emotional Intelligence, Problem Solving, Presentation Skills, Time Management, Interpersonal Skills, Marketing, Goal setting, Social media and Leadership & Management. Skills Zone Malta also offers mentoring programmes with a special focus on women. SZM to date is involved in 12 projects funded under Erasmus Plus.

MÖEUOIII

MÖEUOIII (Manisa Özel Eğitim Uygulama Okulu III. Kademe), is a special education school that educates individuals (age 14- 21) with intellectual disabilities. They have a secondary school for kids (age 9-14) and there are almost 50 teachers work together for over 100 students with various special needs. With another special unit of another VET school, there are three special education schools under the same roof.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This web page and all its content reflects the views only of the author and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

RESULT 1: THE REASERCH

We conducted an investigation on four different fields (LGBT+ community, gender inequality, disability and racism). We investigated how different countries of the EU are dealing with battling the injustices and how are they improving approaching this problem.

Finally, our research is over and we can share our reasearch with you all. We hope it will serve not only us, but also others.

The campaign will serve us to raise awareness in the local community and international community. With it we want to share stories, experiences and hopefully connect people. We want to raise awareness, break the stigma, speak and be heard and include everyone that wants to participate. Follow our social media @euqualizer and join our events!IF YOU WANT TO SHARE YOUR STORY, contact us!

The creation of the toolkit is an important tool for educators to implement the problem of stereotypes into their daily learning activities. We will create a MOOC, composed of 5 modules:

1. introduction to the topic

2-5: LGBT+, racism, gender inequality and disability: theoretical part and an interactive and practical one based on the principle of non-formal education activities.The MOOC will be available for download of the toolkit for free, once created.

In addition to disseminating the results of our research and the materials produced on dedicated social media pages, we have organized a series of local events in each of the project's partner countries with the aim of creating an awareness campaign on the four key areas of EUqualizer (LGBT+, racism, gender inequality and disability) that could resonate at both national and international levels.

RESULT 2: AWARENESS CAMPAIGN

Activity 1: Local events

TURKEY

The Turkish team held several events in Manisa (Turkey) including a dissemination event specifically designed for University students working as interns in the social services department working in their school and parents of their school students. The aim of the event was to provide interns and parents with practical tools and resources for promoting diversity, inclusion, and equality in their classrooms.

The event was well attended, with 30 interns and parents participating. Participants expressed their appreciation for the opportunity to learn from experts in the field and to connect with colleagues or parents who share their passion for promoting diversity, inclusion, and equality in the classroom. Many participants commented on the importance of events like these in promoting greater understanding and empathy among students.

MALTA

The Malta Team created a Trans* Campaign online, using all the social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, and YouTube). It was especially significant for the project to make the older generations more aware of the issues as they are often confused about how someone can change their gender or even what gender is in the first place. When it comes to younger generations, they are more aware of it, and this campain aimed to make them more active in social issues, such as transgender rights.

In their campaign, they collaborated with a local activist, Nik Keter (he/they), who told them his story to share on our social media. Nik Keter is a trans* artist, student, activist, and yoga teacher. From a young age, he has been heavily influenced by psychology, mythology, and religion (mainly Catholic and Hindu practices), which remain prevalent in their work today.

As a part of their collaboration with Nik Keter, they also decided to do an interview with him and ask about 4 essential issues:-When did you start feeling that your gender may not match the one assigned at birth?

-How did you feel about it?

-How did you come up with ideas for your pieces of art?

-How do you want to influence people with your art?

FINLAND

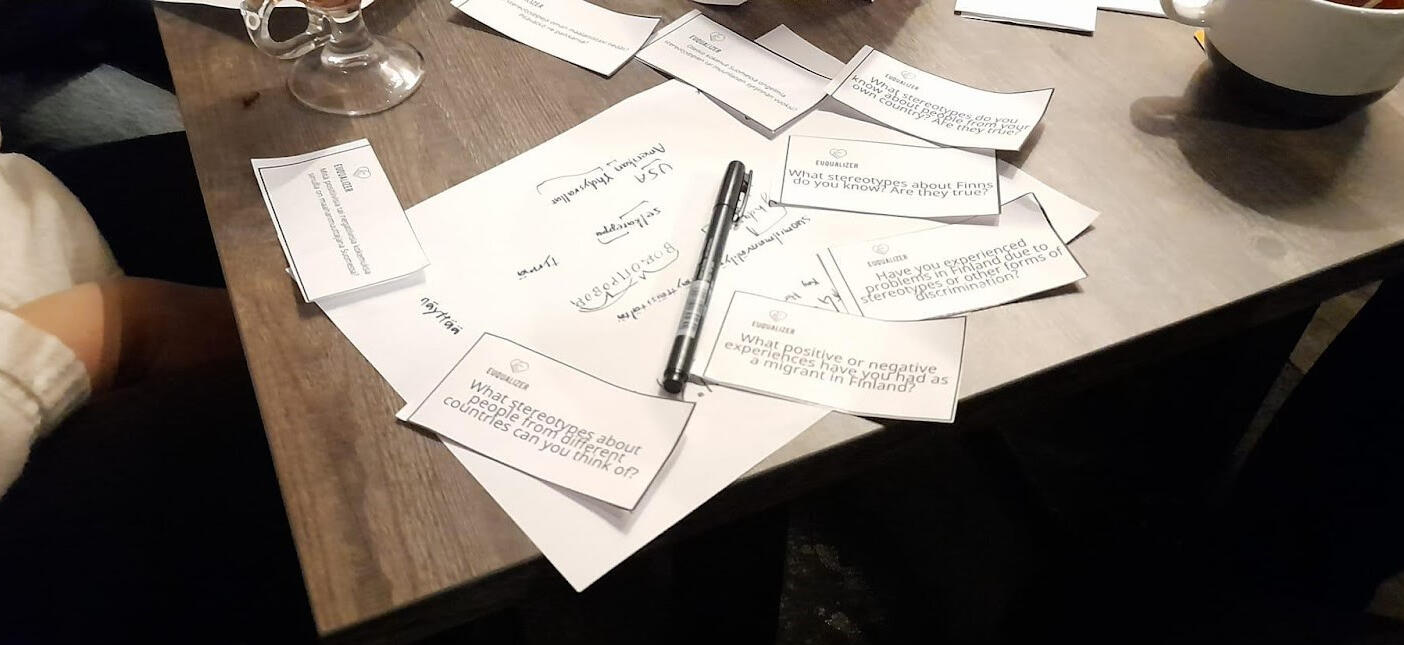

The Finnish team held several events including a discussion in their Café Lingua that usually has 20-30 people practising speaking in different languages, the majority of participants are foreigners studying or working in Finland.

They made discussion cards related to the topics of EUqualizer project discussing stereotypes people in Finland have about their countries or other countries, and the stereotypes they have about Finnish people, as well as their experiences as a foreigner in Finland. The participants in the discussion group were both foreigners and native Finns, and a lot of cultural issues were brought up.

Many thought that, as the stereotype suggests, Finns are quite quiet and it is difficult to form social relationships with them, even though in general they are also very helpful and friendly. Differences in temperament, concept of time and other such issues caused misunderstandings, although most of them also had many positive comments about living in Finland.

ITALY

The Italian team held several events, including one at CasArcobaleno (Turin). They hosted a talk by Elisa Costantino and Marina Granata, two activists on disability and neurodivergences. They are part of the “MAI Ultimi” student collective in Turin. They gave a speech on the multiple kinds of discrimination on discrimination faced by people with physical/mental disabilities and neurodivergent people in Italy, exploring many aspects of the youth’s life and giving insights on their own lives.

The talk was interactive, they had many questions coming from the audience. Only a small part of the audience was made up of people with disability and the rest of it was made up of queer people who wanted to know how to be good allies. There were 15 attendees. The event was made accessible to deaf people thanks to an interpreter.

SPAIN

We (spanish team) organized several events in secondary schools including one in IES Ribadeo Dionisio Gamallo, Ribadeo (Lugo).

We had the opportunity to talk to young people between the ages of 14 and 16 about the topic of stereotypes and inequality. After an initial explanation of how the idea of the EUqualizer project was born and how it has been developed so far, we tried to understand how much young people really knew about the 4 areas discussed in the EUqualizer project (gender equality, racism, disability and LGBTQ+). In fact, we made the activity more playful by telling young people to scan a QR code that referred them to a quiz we prepared where they were asked questions about the 4 areas.

We (spanish team) organized several events in secondary schools including one in IES Ribadeo Dionisio Gamallo, Ribadeo (Lugo).

We had the opportunity to talk to young people between the ages of 14 and 16 about the topic of stereotypes and inequality. After an initial explanation of how the idea of the EUqualizer project was born and how it has been developed so far, we tried to understand how much young people really knew about the 4 areas discussed in the EUqualizer project (gender equality, racism, disability and LGBTQ+). In fact, we made the activity more playful by telling young people to scan a QR code that referred them to a quiz we prepared where they were asked questions about the 4 areas.

Activity 2: Online petition

Among the results of this phase of the project, the team created an online petition for the establishment of an INTERNATIONAL DAY AGAINST STEREOTYPES of any kind.Scan the QR code to help us with our signature collection.The petition can also be find by clicking here!

Activity 3: Online awareness campaign

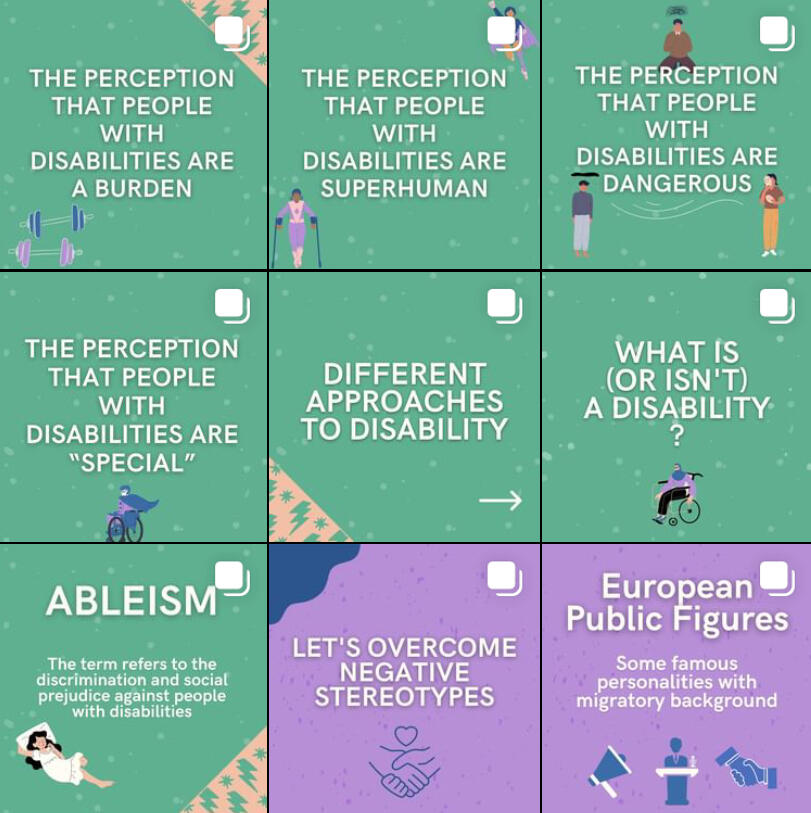

We have created an awarness campaign online (5 months- 1 topic per month; stereotypes, disability, gender equality, LGBTQ+ and racism) where each partner had to create 1 quiz and 9 posts. You can also have a look at the blog posts we have written (one for each of the previously established fields: LGBTQ+, gender equality, racism and disability) in the ‘blog’ section of the webpage.

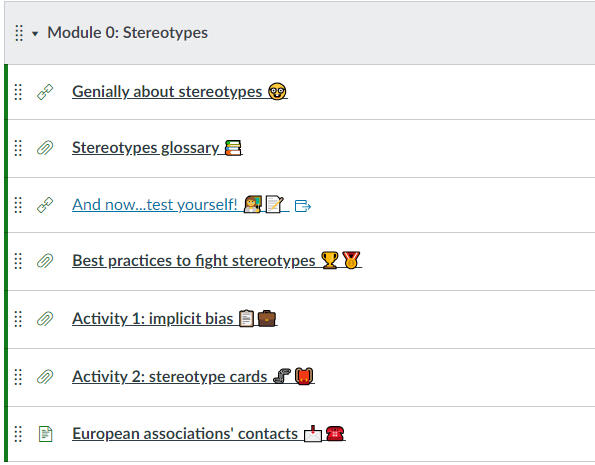

RESULT 3: TOOLKIT FOR EDUCATORS (MOOC)

During the final implementation phase of EUqualizer, we created a MOOC, a useful tool for educators to address the issue of stereotypes during their daily work with young people.

The MOOC is divided into 5 modules (Stereotypes, Disability, Gender equality, LGBTQ+ and Racism) that follow the same structure:-glossary

-kahoot

-best practices

-2 activities

-European Associations' ContactsBelow you will find links to access the MOOCs in the different languages (English, Italian, Spanish, Finnish and Turkish)

Your contribution is very important to us! Help us improve our tool by accessing the MOOC directly through the provided link and giving us a feedback through this Google Form.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This web page and all its content reflects the views only of the author and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

EVENTS

A Coruña, 17-19.3.2022

1st TRANSNATIONAL MEETING IN A CORUÑA, SPAIN

In March the whole team of EUqualizer met in the beautiful, coastal town in the north of Spain; A Coruña. The transnational meeting served us not only to work on the tasks related to the project but also to get to know each other better and to start a beautiful cooperation between 5 countries participating in this 2 year project. The meeting served to us to define all the future results we want to achieve within this project and share it with you. The first result will be a research on the topic of different stereotypes and marginalised groups in Europe and how the current situation is in regard the 4 fields we are working on.Stay tuned for more news coming up soon! :)

Helsinki, 1-3.9.2022

2nd TRANSNATIONAL MEETING IN HELSINKI, FINLAND

In September the EUqualizer team met in the cold north - we visited Helsinki, where our partner Learning for integration ry is based. The visit was marked by the end of the research, we have been working on the past few months. Each partner was researching 5-6 countries of the EU, with the focus on the fields of LGBTQ+, disability, gender rights and racism and how each partner is dealing with it. During the meeting we have marked the following 6 months, which will be centred around a campaign to raise awareness on stereotypes and to include people from our local communities. In the next following months you can expect a lot of social media posts (if you don't yet follow us on Instagram, this is the sign that you should), blog posts on our website and in-person events, we are all so looking forward to.

Manisa, 13-15.3.2023

3rd TRANSNATIONAL MEETING IN MANISA, TURKEY

In March the EUqualizer team gathered in Manisa, Turkey, where our partner Manisa Özel Eğitim Uygulama Okulu III. Kademe is based. The visit was marked by the end of the awareness campaign carried out by each partner in their own country. During the meeting, we established the tasks to be completed during the final implementation phase of the project. A template was designed to guide the creation of the MOOC on Canvas, toolkit for educators and professionals in the four fields of the project to implement the topics into their daily learning activities. Specifically, tasks were divided among all the partners, and a plan for the dissemination of the MOOC was established. The progress of the online petition for the International Day Against Stereotypes was also monitored, and a new signature collection strategy was developed.

Turin, 9-11.11.2023

4th TRANSNATIONAL MEETING IN TURIN, ITALY

In November the EUqualizer team gathered in Turin, Italy, where our partner Arcigay is based. The fourth and final meeting follows the last phase of project implementation, the creation of the MOOC. All partners were invited, through Mentimeter, to provide a personal assessment of the project as a whole. Tasks to be carried out in the final phase of the project were established, providing a template for disseminating the MOOC and collecting feedback from students and educators through specific Google Forms.Stay tuned for updates on the petition for International Day Against Stereotypes on change.org. :)

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This web page and all its content reflects the views only of the author and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

BLOG

La Coruña, February 2023

**WHAT IS HATRED? **

It is not easy to give a definition to the term “hatred”.

Having a clear idea of what hate means and what its dynamics are, is the first necessary step in order to combat this plague. Although it may seem rather straightforward, it can be challenging to define what hatred is.Even if there is no consensus among scholars about its nature, hate is usually described as an emotion, but also as an attitude or a sentiment.

What is known is that hatred is a complex emotional and psychological feeling of intense dislike (for another person or group). It is intense and enduring, and it seems to be based on a view of its targets as essentially bad and threatening. This deep-seated form of dislike or resentment is typically directed towards someone or something that is perceived as a threat, enemy, or opponent. Therefore, we can safely say that hatred is a form of active, ongoing hostility that uses up significant emotional energy.

The experience of hatred is characterized by a range of negative emotions, including anger, fear, disgust, contempt, and a desire for revenge. It often involves negative stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination towards the target of hatred, which can manifest in various forms, including verbal abuse, physical violence, or exclusion from social groups.To this day, it seems that hating is part of human nature and seems unavoidable.Given the destructive nature of hatred, it is essential to understand its dynamics and work towards combating it. This requires a deeper understanding of the underlying causes and motivations for hatred, as well as a commitment to promoting empathy, tolerance, and understanding toward others.

Reasons that drive us to hate

So… how can one defend oneself from hatred without knowing how to recognize it? Are we aware of the reasons that drive us to hate?

It’s easy to feel conflicted when a colleague or classmate consistently outperforms others, isn’t it? They receive recognition or rewards, they may be promoted and get treated better.

Jealousy may arise among the workers who feel left behind. They might think they did a better job and deserved that promotion, and in a glimpse, they engage in negative talk or gossip. Such actions easily create a toxic work environment that damages relationships and morale.

In the moment people gave into engaging in negative talk, they fed the culture of hatred.

It can escalate further, by having the workers make assumptions or stereotype the successful colleague based on their race, ethnicity, religion, or other personal characteristics. In such a way, they are feeding into prejudice and bigotry that leads to discrimination and exclusion of certain groups and can create an atmosphere of hate.Such atmosphere and culture get fed more by following actions:

When people engage in bullying or harassment, they are feeding into a culture of intimidation and fear. This can cause harm to individuals and can create an environment where people feel unsafe and unwelcome;

When people refuse to listen to others or consider their perspectives, they are feeding into a culture of closed-mindedness and intolerance. This can lead to division and hostility between individuals and groups;

When people refuse to take responsibility for their actions and instead blame others for their problems, they are feeding into a culture of victimization and resentment. This can create a sense of entitlement and a lack of empathy for others.

Overall, when we perceive someone or something as a threat to our happiness, success and well-being, that’s when we start to feel some form of hatred. But such actions steams from not managing emotions in a constructive way: jealousy can be used as a motivator to improve or seek out new opportunities, rather than allowing it to fester into negative feelings towards others.

Also, hatred has some psychological uses: as said before, jealousy is closely linked to hatred. Watching others succeed makes the haters feel inferior, insecure, and useless. In this case, hatred is used as a mean to restore psychological stability.

Also displaying a lack of self-compassion is hatred in the form of reflection. It brings the hater to hate others for what they don’t accept about themselves. Such people may be overly critical of themselves and their actions, leading to and may hold themselves to impossible standards and feel like they can never live up to them, which can lead to feelings of worthlessness and self-doubt. The lack of self-compassion reflects a deeper underlying issue of self-hatred and negative self-image.

By nature, we tend to avoid what we believe has the potential of causing us pain. It is easier to build a wall between us and something we do not comprehend and is hurting us. This wall can be built day by day, brick by brick, with excuses, stereotypes, etc. In these circumstances, we resort to hatred as a pain-avoidance mechanism; and it easily leads to fear.

Hate is an act of fear; fear of connecting with something different. Being taught to hate leaves little room for vulnerability and exploration of hate through empathic discourse and understanding.

Hatred can be used as a toxic way of bonding because it creates a sense of unity among people who share the same negative feelings towards something or someone. When bonding over their shared hatred, they may feel a sense of belonging and validation from others who feel the same way. Toxic bonding often involves dehumanizing or demonizing the target of the hatred, which can lead to harmful behaviors toward them. Additionally, this type of bonding reinforces and intensifies negative emotions, making it difficult for individuals to break away from the group or change their perspective.

The hatred and negative emotions can become a defining aspect of their identity, which can lead to a narrow worldview and an unwillingness to consider alternative perspectives or engage in constructive dialogue. In extreme cases, this type of bonding can lead to groupthink, mob mentality, and even violence toward the object of their hatred.It is important to remember that while it’s impossible to be always positive and that negative feelings are legit, they can be harmful and should be avoided. Healthy relationships and communities are built on positive values such as empathy, respect, and mutual understanding.

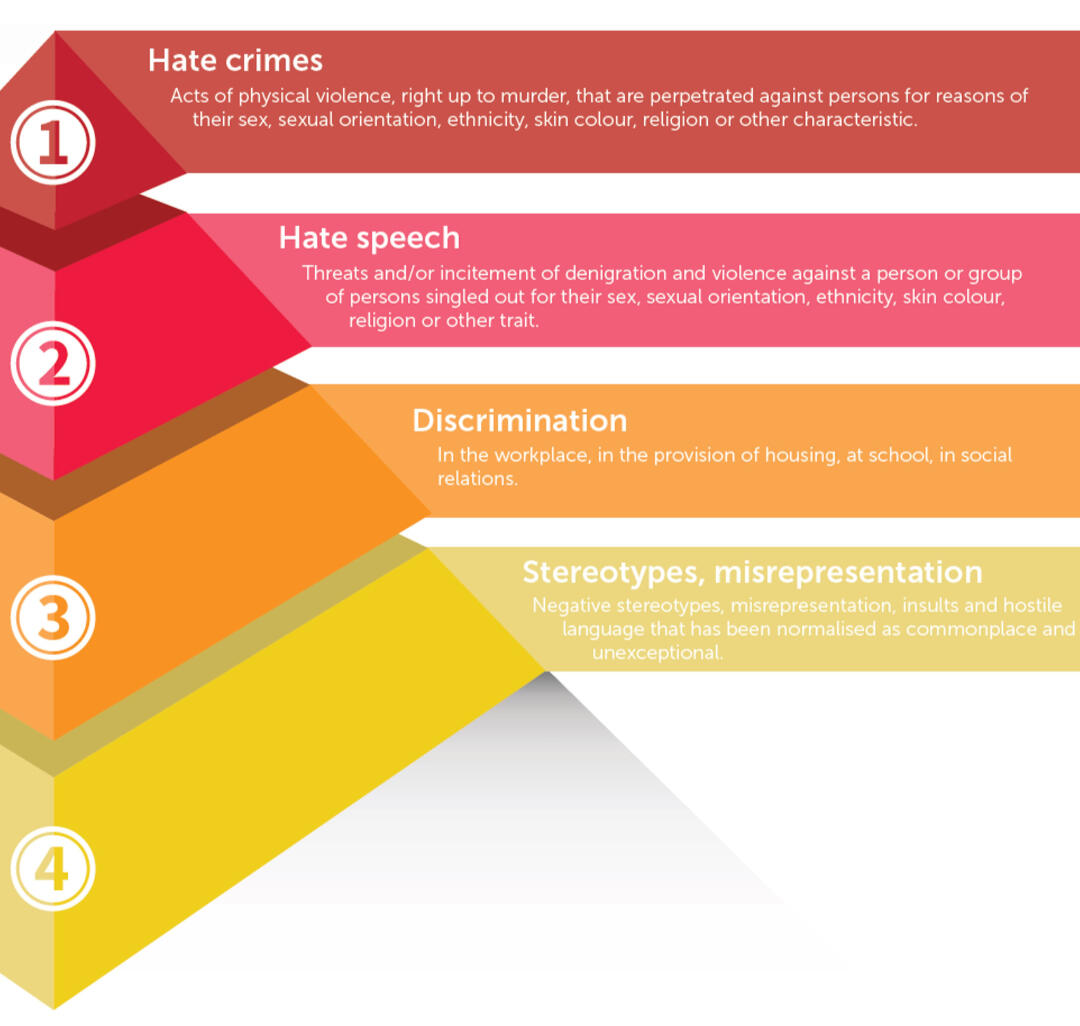

THE PYRAMID OF HATRED

To explore and study the different forms of hatred in society, in May 2016, the Italian parliament established “The 'Jo Cox' Commission on Hate, Intolerance, Xenophobia and Racism”, chaired by President Boldrini. Its members comprise one MP for every political group in the House, representatives of the Council of Europe, the United Nations, ISTAT (Italian Statistics Institute), research centres and civic associations that investigate and campaign against hate speech, and experts.

The final result reported of what is now know as “Pyramid of Hatred”. The committee’s final report presented a pyramid of hatred at the base of which lie stereotypes, misrepresentation, vilification, and hostile language that has been normalised as commonplace and unexceptional. The upper sections relate to acts of violent discrimination.

The pyramid of hatred is the result of the Jo Cox Commission study. Here you can read the full report.

The pyramid of hatred is not an attempt to justify certain behaviours or actions, but is rather a tool that helps understand the severity of the consequences of violent acts. While the pyramid’s lower sections focus on the foundation for hate-based violence, the upper two sections relate to forms of hate-based violence, including hate speech and hate crimes, linked to gender, sexual orientation and gender identity, skin color, race/ethnicity, disability, religion or other personal characteristics.

Exploring the levels

1. Hate crimes

Acts of physical violence, right up to genocide and murder, are perpetrated against people due to their sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, skin color, religion, or other personal characteristics.2. Hate speech

Threats and/or incitement of denigration and violence against a person or group singled out for their sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, skin color, religion, or another personal trait.3. Discrimination

Verbal/non-verbal non-physical acts of violence in the workplace, in the provision of housing, at school, in social relations (like mobbing, social exclusion, etc.)4. Stereotypes, misrepresentation

Perpetration of negative stereotypes, misrepresentation, insults, and hostile language that has been normalized as commonplace and unexpected.

Starting from the bottom, we have stereotypes and misrepresentations. These are the foundation of bias and everybody encounters them both in positive and negative forms. While stereotypes are self-explanatory and were quite explored in our previous blog posts, there is a need to dive deeper into discrimination.Not all discrimination looks the same. In fact, 4 types of discrimination occur in society:

Direct Discrimination: occurs when a person is being treated unfairly because of skin color, nationality, sexual orientation, gender, and/or disability. Mistreatment due to perception or association with people with protected characteristics also falls into direct discrimination.

Indirect Discrimination: less obvious, occurs when a rule or plan applies virtually to everyone, but unintentionally puts people with the protected characteristic at disadvantage.

Harassment: any type of unwanted conduct that has the purpose of creating a hostile, degrading humiliating environment and/or violating a person’s dignity. (ex: bullying, name-calling…)

Victimisation: occurs when a person suffers a loss, disadvantage, damage, or harm because they made supported or gave evidence to an allegation of discrimination. These people get labeled as “troublemakers” and are likely to be ignored, excluded, or denied opportunities.

If we keep seeing hatred as a wall built day by day, then we can say that any action taken everyday helps destroying such wall.

We saw that discrimination can be disguised as jokes or political opinions and that’s why is important to have an open dialogue and listen to marginalized and discriminated people, without pushing our view of the world onto them. Language needs to be minded. It is important to feel accountable and responsible of our and other people actions, by keeping our mind open and fight prejudices and stereotypes.

While it’s important that institutions issue laws and research and publish useful datasets and material, it is also important to keep talking about real people, instead of just numbers. In such a way, it is possible to dust away misinformation and build quality conversations around the topic.

On hate speech & hate crimes

Hate speech refers to any form of speech or expression that attacks or denigrates a person or group based on their personal characteristics, such as their race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, or other defining traits. Hate speech can take many forms, including verbal attacks, slurs, threats, or harassment, and it can be communicated through various mediums, including speech, writing, or online platforms. The primary goal of hate speech is to cause harm to the targeted individual or group by using psychological methods such as intimidation, humiliation, or fear.

Although there is still no universal definition of hate speech, three main characteristics can be attributed to it and are useful for recognising it.

Hate speech can be conveyed through any form of expression, including images, cartoons, memes, objects, gestures and symbols and it can be disseminated offline or online.

Hate speech is “discriminatory” (biased, bigoted, or intolerant) or “pejorative” (prejudiced, contemptuous, or demeaning) of an individual or group.

Hate speech calls out real or perceived “identity factors” of an individual or a group, including “religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, color, descent, gender,” but also characteristics such as language, economic or social origin, disability, health status, or sexual orientation, among many others.

Especially in the aftermath of the pandemic, that has forced us all to limit human contact and resort to technology in order to bridge the distance and gaps in our days, hatred has found in online platforms an excellent ally for its expression. People anonymously can post anything online. Online hate speech can be produced and shared easily, at low cost and anonymously. It has the potential to reach a global and diverse audience in real time.

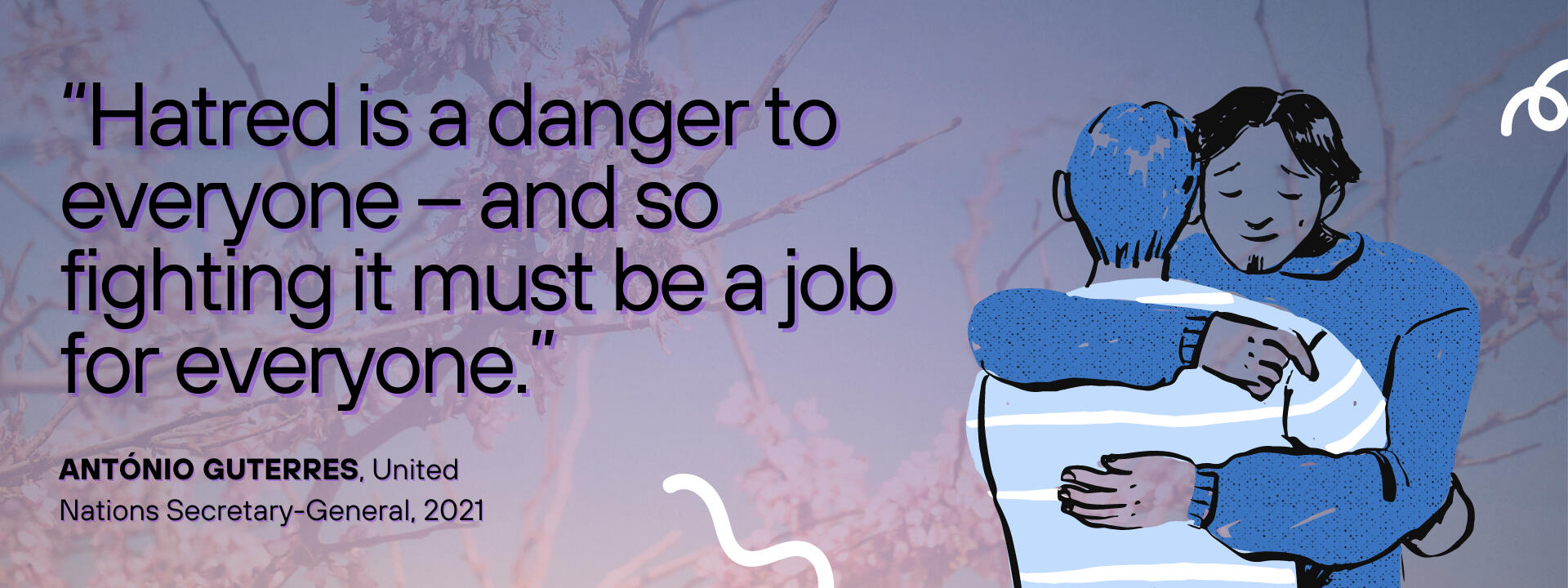

As a response to the phenomenon of online hate speech the United Nations and the Secretary-General António Guterres have taken several actions with the aim of actively contributing to reducing the rate of online hatred.

United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech was launched on 18 June 2019. The goals of this plan of action are two:

enhance UN efforts to address root causes and drivers of hate speech;

to enable effective UN responses to the impact of hate speech on societies.

The Strategy and Plan of Action consists of 13 commitments for action by the United Nations system and is grounded on four key principles:

The strategy and its implementation are in line with the right to freedom of opinion and expression. Therefore UN won't support less freedom of speech nor hate speech;

Tackling hate speech is the responsibility of all – governments, societies, and the private sector, starting with individual women and men. All are responsible, all must act;

In the digital age, the UN should support a new generation of digital citizens, empowered to recognize, reject and stand up to hate speech;

There's the need to know more to act effectively – this calls for coordinated data collection and research, including on the root causes, drivers, and conditions conducive to hate speech. It also includes ways the UN Secretariat can support the work of the Resident Coordinators in addressing and countering hate speech.

Reference: United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech

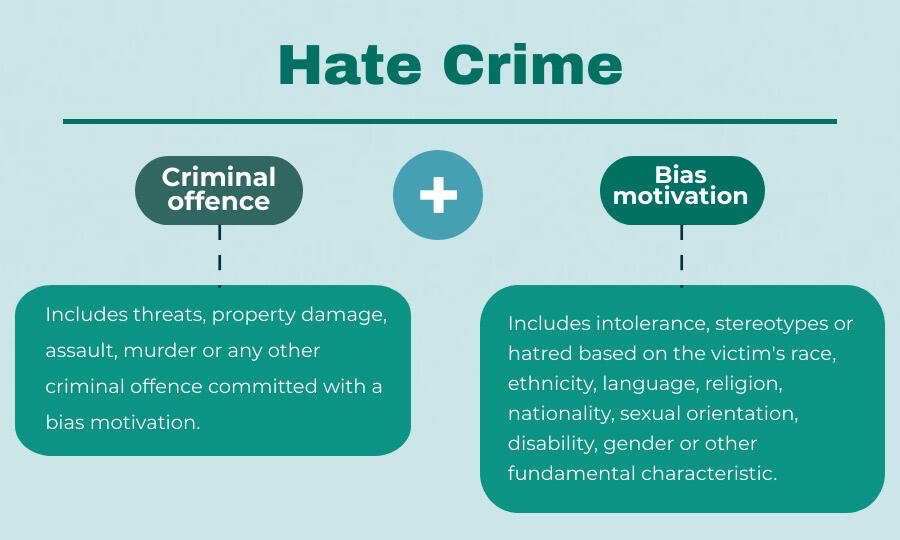

While hate speech focuses on damaging people through harmful psychological methods, hate crimes are violent acts that are motivated by bias or prejudice against an individual or group based on their personal characteristics. These crimes are typically directed at individuals or groups that are perceived to be different from the perpetrator or to be part of a marginalized community, bias/prejudice is put upon one or multiple personal characteristics such as ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, etc. People who display more than one personal characteristic are at a higher risk of getting harassed.Hate crimes fall into 3 different categories:

physical assault

verbal abuse

incitement to hatred

Examples of hate crimes include physical assaults, vandalism, arson, and even murder. The gravest level is genocide.The common thread between hate speech and hate crimes is the role of prejudice and bias in motivating harmful behavior. While hate speech primarily uses psychological methods to cause harm, hate crimes involve physical violence or destruction. It is important to note that both hate speech and hate crimes are serious problems that can have lasting consequences for individuals and society as a whole. Combating these issues requires a concerted effort to promote understanding, tolerance, and respect for all individuals regardless of their personal characteristics.

The difference between bias-motivated crime and bias incident

Hate crimes are often referred to as “bias-motivated crimes”, since the core motivation behind them is to physically harm or intimidate the targeted individual or group because of their personal characteristics.

While bias-motivated crimes are accounted as criminal offences, bias incidents comprehend any hostile expression motivated by another’s personal characteristic. Name-calling, dead-naming and slurs, imitating harmful stereotypes, and creating racist content are all valid examples of bias incidents.

The effects

People victimized by hate crimes not only will have to deal with the consequences of the crime itself, but are going to suffer from psychological distress, like PTSD, depression, anxiety, safety concerns, panic, self-blame, and might reiterate a feeling of mistrust in people and isolation/abandonment.

The impact of hate crimes affects indirectly the community of which the victim is part. The social perception might change and create tensions inside and outside the community, increasing the feeling of being vulnerable.

WHAT'S BEING DONE AGAINST HATE CRIMES?

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union was proclaimed on 7 December 2000 and started having full legal effect for all EU State members with the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009.

Articles 1, 10, 21, and 47 of the Charter guarantee:

the right to human dignity;

freedom of thought, conscience, and religion;

the principle of non-discrimination;

the right to an effective remedy and a fair trial.

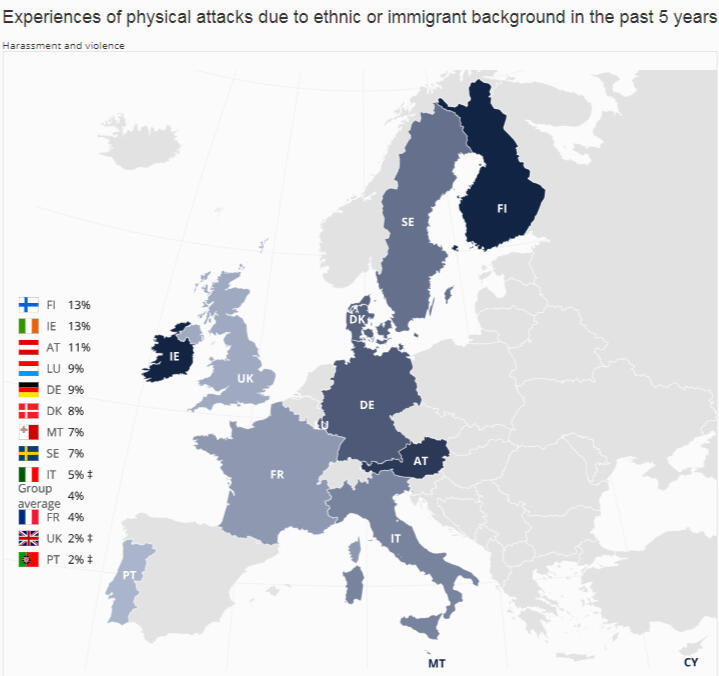

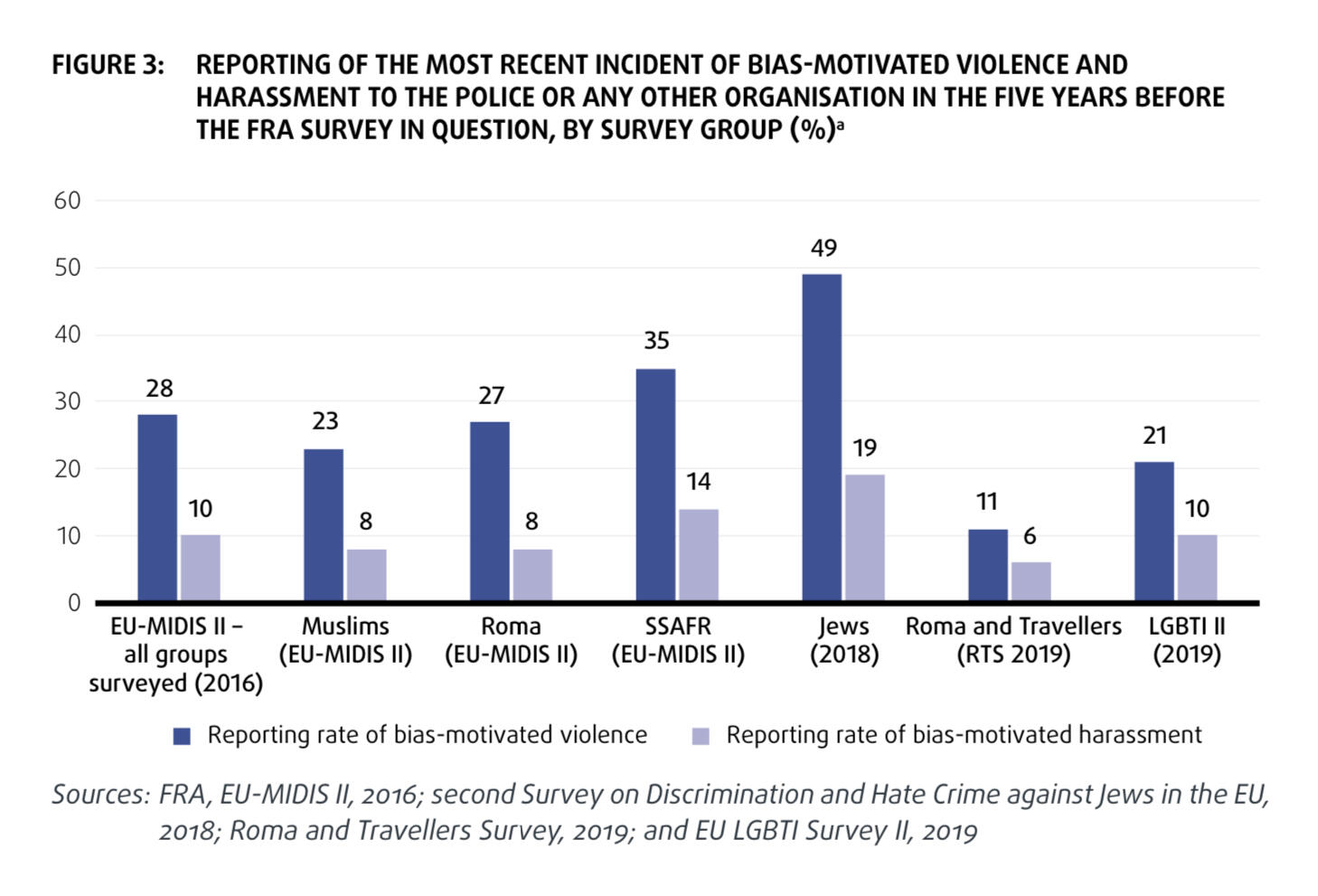

Even if the Charter is quite clear about the rights that should be guaranteed in the EU, several FRA (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights) reports and surveys state that 9 on 10 hate crimes that happen inside the EU don't get reported to the authorities.

The report states that: “Between 30 % and 49 % of respondents to the FRA surveys had experienced some form of bias-motivated harassment in the five years before the surveys were conducted – be it because of their ethnic or immigrant background, their skin color, their religion or religious beliefs, or being LGBTI.”

It is to be noted if there’s more than one personal characteristic there’s a higher chance of getting harassed.

REPORTING IS DIFFICULT

Hate crimes are a pervasive problem in society, with many individuals experiencing incidents of hate or bias on a regular basis. As said, these crimes can take many forms, including physical assault, vandalism, threats, and harassment. Despite the prevalence of hate crimes, many individuals do not report these incidents to law enforcement.

One of the primary reasons hate crimes don’t get reported is fear of retaliation.

The people who experience them are members of marginalized communities, and they fear further violence or harassment if they speak out. Also, there’s the risk of being marginalized further. Some individuals don’t report because they do not want to draw attention to their identity - as they may already experience discrimination or harassment in other areas of their lives.This fear can be compounded by a lack of trust and faith in law enforcement to protect them. Negative experiences with police in the past, media communication, corruption, and general stereotypes may be some of the reasons why law enforcement faces such distrust. As a result, members of marginalized communities may be hesitant to engage with them. They may feel that law enforcement does not take hate crimes seriously, are very biased, or that they will not receive a fair outcome if they do report.Furthermore, there’s a general sense of hopelessness and disillusionment with the justice system itself. They believe that the system will not provide them with the outcome they desire or that they think it’s just. Marginalized people and victims may feel that the offender will not be held accountable or that the punishment will be insufficient. Also, there's a fear of not being able to provide the funds to face a just trial.Finally, some individuals may not report hate crimes because they are not aware that what they experienced is considered a hate crime. Many people may not know what qualifies as a hate crime, and as a result, they may not recognize that they have been victimized in this way.

Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach that involves educating the public, building trust between marginalized communities and law enforcement, and ensuring that hate crimes are taken seriously and prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.Although the report notes a low tendency to report is also common among victims of non-bias-related violence: less than a third of those who suffer a physical assault file a complaint.In conclusion, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights recommends the promotion of anonymous/third-party reporting, specific training for the police, or the creation of specialised hate crime units. Promoting diversity within the police and regular public communication on hate crime statistics are also seen as useful tools to raise public awareness on the issue and promote reporting in case of violation.

**So… Is hatred a learned behaviour? **

The bad news is: yes, hatred is a learned behavior. We are products of the environment and social group we grow in, thus how we see people behaving and talking around us shapes inevitably parts of our behavior.

The good news is… it is unlearnable.

How? By educating ourselves and being truthful. Talking about differences won’t automatically increase prejudice against specific groups; in fact, being aware of differences increases sensitivity and shouldn’t be seen as the same as avoiding, ridiculing, or fearing.

Things you can do daily to fight hate

Educate yourself: dig deeper within yourself and acknowledge internalized biases and stereotypes. It’s a scary and difficult journey, but the good news is acceptance and compassion (for yourself and others) are learnable behaviors;

Pressure the political leaders: create connections between them, you, and the community, pressure them to not ignore or condone hateful acts;

Support the victims: speak up even if you might go against conformism, help victims report, ask for help, and surround them with understanding and protection)

Ask people what they really need and listen to them;

Avoid the bystander effect: do not assume someone will step in, take a moment to breath and step in the situation when necessary;

Be kind (to yourself and others): social battles can be exhausting and do take a toll on everybody. Therefore don’t forget to take care of yourself.

Authors:

Pamela Venuti

Grazia Mariani

Valletta, January 2023

WHAT IS GENDER?

Most of the people grew up learning that there are just two genders: man and woman. However, the concept of gender is much more complex than that.The Council of Europe’s Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence was the first international document to include a definition of gender. In Article 3, gender is defined as “socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women and men.”

Therefore, gender is challenging to properly define, as it refers to various socially and culturally constructed characteristics of sex – such as norms, roles, and relationships of and between groups of women and men.

It means that even though people are born either male or female, they are taught appropriate norms and behaviours – including how they should interact with others of the same or opposite sex within households, communities, and workplaces. When individuals or groups do not fit into the established gender norms they often face discriminatory practices or social exclusion – all of which adversely affect health, especially mental health.For most people, their gender identity matches the gender they're assigned at birth. However, there are also people who transition from one gender to another, experience gender between the binaries or find that their gender is completely outside the binary.In fact, the understanding of gender continually evolves. In the course of an individual’s life, the interests, clothing and professions that are considered the domain of one specific gender evolve in various complex ways.

Gender

=

Gender identity

(one’s internal sense of gender)

+

Gender expression

(external manifestation of gender)

To understand the difference between three terms – sex, gender, and sexual orientation – one must first understand what gender is.A person's gender is what they socially identify as. A person may decide this based on their role and behaviour. Gender identity refers to a person's "deeply held sense of their gender." When a person's gender is the same as their sex, they are called as cisgender. Those whose gender is different from their sex are known as transgender. Yet, gender is a spectrum rather than a binary.

Interestingly, people tend to use the terms sex and gender interchangeably. But, while connected, the two terms are not equivalent.A person's sex relates to their physical and biological features. This includes their sexual anatomy, chromosomes, hormone levels, and genes. Therefore, sex is assigned at birth, and there are two sexes: man and woman.One final distinction to make is the difference between gender and sexual orientation, which are often incorrectly conflated. In reality, gender and sexual orientation are two distinct, but related, aspects of self.

Sexual orientation is defined as sexual orientation, sexual activity, and capacity for sexual feelings. Homosexuality, heterosexuality or bisexuality are examples of sexuality. Just like gender, sexuality is a spectrum.

Sexuality is not a choice.Simply put: Sexual orientation is about who you are attracted to and fall in love with; gender identity is about who you feel you are; and sex is a biological feature assigned at birth.

Issues of equality and acceptance of people of all genders — along with challenges — have become a major topic in the headlines. These issues can involve words and ideas and identities that are new to some. Therefore, it is significant to understand the most common gender terms.

GENDER

A person's gender is what they socially identify as. Gender identity refers to a person's deeply held sense of who they are in terms of gender.SEX ASSIGNED AT BIRTH

The sex (male or female) assigned to a baby at birth, usually determined by external anatomy and genetics.QUESTIONING

A term describing someone who is exploring and trying to understand their sexual orientation or/and gender identity.GENDER IDENTITY

The way an individual perceives themselves and identifies, in terms of gender. This may or may not align with their sex assigned at birth.GENDER EXPRESSION

The physical expression of an individual's gender identity, for instance, through clothing and behaviour. This is based on socially defined characteristics which usually correlate with the western definitions of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’.GENDER TRANSITION

The process that an individual goes through to match their physical appearance to their gender identity. This can include surgeries, changing names, pronouns, clothing, and taking hormones.CISGENDER

A term for people whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.NON-BINARY

A term assigned to individuals who don't identify with the gender binary (the concept that there are only two genders). This term can be used to describe people who identify as agender, bigender, genderqueer or gender-fluid.TRANSGENDER

A general term for people whose sex assigned at birth does not match their gender identity.DEAD NAME

The name given at birth for people who have changed their name. Most often, it is applied to transgender individuals.GENDER DYSPHORIA

Clinically significant distress caused when a person's assigned birth gender is not the same as the one with which they identify.GENDER FLUID

Someone who does not fall into the categories of ‘man’ or ‘woman,’ or has a fluid or unfixed gender identity.GENDER-EXPANSIVE

A person with a more flexible range of gender identity or expression than typically associated with the binary gender system. It's usually used to refer to people who are still exploring the possibilities of their gender expression and/or gender identity.GENDER-QUEER

People who typically don't conform to the categories of gender and embrace a fluidity of gender identity. They can see themselves as being both male and female, neither male nor female or may not fall into any of these categories.GENDER VARIANT

Someone who does not conform to gender-based expectations of society.TWO-SPIRIT

A term traditionally used by Indigenous peoples to describe individuals who fulfill a traditional third gender.ANDROGYNOUS

An individual who identifies or presents as neither distinguishably masculine nor feminine.INTERSEX

Individuals who are born with differences in genitalia, chromosomes, gonads, internal sex organs, hormone production, hormone response, or secondary sex traits.AGENDER

Someone who doesn't have, or identify with, a gender.BIGENDER

An individual who shifts between the binary "male" and "female" gender-based behaviours and identities.MX.

A title, like Mr. Ms., that is gender neutral.

Remember, no matter what gender you are,

you can dress, look, and live anyway you want!

Patriarchy refers to a system of political, social, and economic relations and institutions structured around the gender inequality of socially defined men and women. Women are excluded from full participation in political and economic life within patriarchal ties. Those attributes seen as ‘feminine’ are undervalued. Patriarchal relations include the private and public spheres, with men dominating both domestic and public life.1 in 4 women and 1 in 26 men are victims of attempted or successful rape but 15 out of 16 rapists walk free. Such a situation is caused by a mixture of factors, including:

a growing victim-blaming culture (e.g., "what were you wearing?");

survivors' shame and fear to report due to public stigma surrounding sexual violence, for both men and women;

law enforcement & justice systems that don't convict abusers adequately.

Moreover, there is also a case that 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men have faced physical violence at the hands of their partners at some point in their lives. Men are less likely to recognize or report their abuse, whilst women are more likely to experience severe and repeated abuse.

Yet, one needs to understand that patriarchy is affecting negatively not only women but also men. In 2020, 3.88x more men committed suicide compared to women. This is largely due to stigma surrounding mental health and the patriarchal notion that men should contain their emotions to be perceived as '"strong" and "masculine".

These are only a few examples out of many more. Yet, they still show that patriarchy is harmful. Toxic masculinity, gender roles and gender stereotypes affect everyone.Patriarchy does not discriminate.

Toxic masculinity is a form of socially constructed gendered behavior that defines manhood. Strength is what dictates the correct way to be a man, whereas emotional vulnerability equals cowardly weakness. Such gender norms mean that men must be physically and emotionally 'strong' and anti-feminine, making them manly' and masculine.

COMMON BEHAVIOURS OF TOXIC MASCULINITY:

Seeing women as weak and not as intelligent as men, as intelligence is seen as masculine.

Men feeling as if they need to be dominant - sexually, intellectually, and physically.

Overwhelming sense of self-reliance – men should not ask for help

Avoiding emotional expressions

Fearing shame from others

Extreme obsession with physical, intellectual and sexual dominance

Devaluing the opinions, body, and sense of self in women

Condemning anything "feminine' and equating affection for sexual attraction in other men

Seeing anything remotely feminine as negative because women are seen as emotional and weak

COMMON PHRASES ROOTED IN TOXIC MASCULINITY:

Real men don't cry

Stop acting like a girl

You need to man up

He bullies you because he likes you

Boys will be boys

Men can’t be feminists

TOXIC MASCULINITY IS NOT:

An assertion that men are bad, evil, or naturally violent

An "anti-male” phrase that claims all men are toxic

A description of masculinity as a whole

TOXIC MASCULINITY IS:

A conversation that discusses why these beliefs exist in the first place and how they can be dismantled

Toxic masculinity, together with all of its characteristics and unrealistic standards, can lead to things such as mental health problems or can lead to men becoming domestically or sexually violent.

**Each of us should know that a man CAN be MASCULINE and

wear a dress, cry, ask for help, wear makeup, or be submissive.

**

Gender stereotype refers to a perception that is considered normal and appropriate for a particular gender. It is also perceived as over-generalization of the characteristics of a gender that has both social and economic impact.Research has shown that gender stereotypes affect everyday personal interactions and form gender disparity in jobs, authority, salaries, and family responsibilities.

**EXAMPLES OF GENDER STEREOTYPES DURING CHILDHOOD: **

Boys are better at math!

Girls like dolls and boys like race cars!

Girls should wear pink and boys wear blue!

Girls should be more nurturing!

Girls should be well behaved while boys can rebell

Stem is not a good career path for girls!

Thin girls are attractive!

EXAMPLES OF GENDER STEREOTYPES DURING ADULTHOOD:

Women are not supposed to marry men younger than them

Real men don't cry

Women should get married before 30

Men who are not aggressive enough are gay

Women who are not interested in dating men are lesbians.

Men who wear pink are gay

A gender non-conforming person is profoundly wrong.

Same-sex couples do not make good parents

Men are breadwinners of the family

Educational and professional advancements shouldn't be important for women

THE CONSEQUENCES OF GENDER STEREOTYPES:

Gender Stereotypes gauge potential, performance, and ambition based on physically apparent differences alone.

The aforementioned study also found that boys and girls, by the age of six, already believe that men are smarter than women.

Men who are emotional and don't meet the stereotype tend to be seen in a negative light which drains them mentally and emotionally („they are not real men”).

According to research, girls begin to feel less intelligent than boys from the age of six.

**WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT GENDER STEREOTYPES? **

A problem arises when gender stereotypes limit a person from being who they truly are. But there are certain ways to fight with these stereotypes, for instance:

Be more aware through educating yourself and changing your mindset.

Speak up if someone makes sexist jokes or comments.

Point out the negative gender stereotypes published by media.

Have an open conversation with our friends/family and make them understand the consequences.

Don't let someone's gender determine their capacity.

Normalize boys wearing skirts as much as girls wearing pants.

Include gender equality in the education of schools.

Respect people regardless of their gender identity.

Create a safe space for people to express themselves.

Question stereotypes that are considered normal but are just social constructions.

"I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own." Audre Lorde on feminism

Feminism is a movement that aims to put an end to sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression and to achieve full gender equality in all areas of life.Although feminism benefits everyone, its main aim is to achieve equality for women, because prioritizing those who are most oppressed means freeing everyone else.Interestingly, although women's rights have come a long way in the past 100 years, the idea that women are now completely equal and no longer need feminism isn't true. Of course, women have much more social, political, and economic rights than before. However, the fact is, women still have to deal with the harmful side effect of gender inequality on a everyday basis.

Here are some examples why we all need feminism:

Not one single country is set to achieve gender equality by 2030.

There is a huge wage gap between men and women.

132 million girls around the world are denied education.

99% of victims of sexual trafficking are girls.

Black women are paid 63% to every dollar a white man earns.

81% of women experience some form of sexual harassment in their lifetime.

Globally, 214 million women still can't get a hold of modern contraception.

Men still believe that they cannot express their feelings.

Men still do not participate as much as women in raising children.

Most of women’s work is unpaid.

The representation of women in politics is still too low.

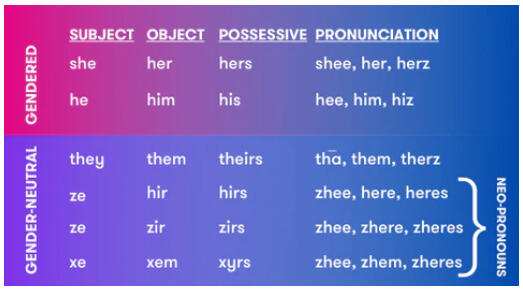

A person's pronouns convey their gender identity. Therefore, there are two types of pronouns: gender and gender-neutral pronouns. A gender neutral/inclusive pronoun is a pronoun which does not associate a gender with the individual who is being discussed.

Some examples of gender and gender-neutral pronouns:

TIPS TO USE PRONOUNS CORRECTLY

The following tips might help you better understand gender pronouns and how you can affirm someone’s gender identity:

Don’t assume another person’s gender or gender pronouns

Ask a person’s about their pronoun

You can’t never know what someone’s gender pronouns are by looking at them, by their name, or by how they dress or behave.

Normalise the sharing of gender pronouns by actively sharing your own – for instance, you can include them on your social media accounts.

Apologise if you call someone by the wrong pronoun

Asking about and correctly using someone’s gender pronouns is an easy way to show your respect for their identity.

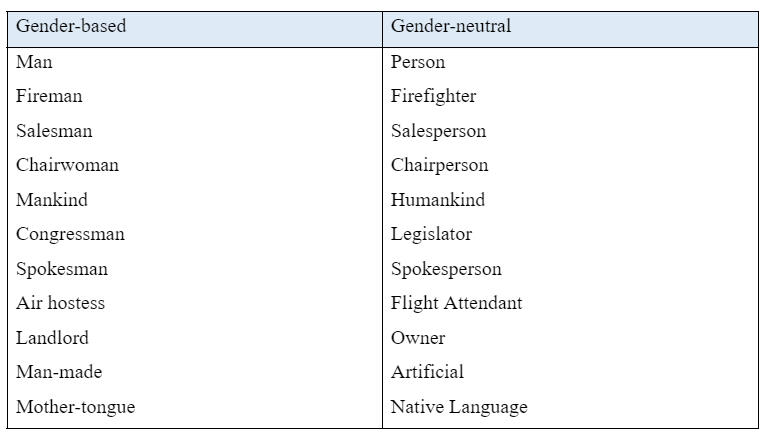

Make you language gender-inclusive

Give yourself time to practise and get used to pronouns you haven’t used before.

Help others use a person’s correct pronouns.

"Using gender-inclusive language means speaking and writing in a way that does not discriminate against a particular sex, social gender, or gender identity, and does not perpetuate gender stereotypes. Given the key role of language in shaping cultural and social attitudes, using gender-inclusive language is a powerful way to promote gender equality and eradicate gender bias."

United Nations on Gender-Inclusive Language

There are many different gender expressions, so everyone should try to avoid using binary language that assumes there are only two genders.

EXAMPLES OF GENDER-INCLUSIVE LANGUAGE

Language has a key role in shaping cultural and social attitudes; therefore, the use of gender-inclusive language is a powerful way to promote gender equality and eradicate gender bias!

Author:

Dagmara Dabek

Ankara, December 2022

DISABILITY-BASED DISCRIMINATION IS STILL ON AS AN IGNORED ROUTINE IN OUR COMMUNITIES

Discrimination against individuals with disabilities continues to be a severe and pervasive social problem. Discrimination against individuals with disabilities persists in critical areas such as employment, housing, public accommodations, education, transportation, communication, recreation, institutionalisation, health services, voting, and public services.

People with disabilities constantly face different kinds of discrimination, such as intentional exclusion, the effects of architectural, transportation, and communication barriers, overprotective rules and policies, failure to make changes to existing facilities and practices, exclusionary qualification standards and criteria, and segregation and relegation to lower services, programmes, activities, benefits, jobs, or other opportunities. Census data, national polls, and other studies have shown that, as a group, people with disabilities have a lower status in our society and are severely disadvantaged socially, in the workplace, financially, and in school. The right goals for the EU for people with disabilities are to ensure they have the same chances as everyone else, can fully participate, live independently, and support themselves financially.

Discrimination refers to the act of treating someone or something differently and is not necessarily negative. To say that someone is discriminating can mean that the person has good taste or judgement. However, discrimination can also mean that someone treats certain people unfairly because of those people’s characteristics. It is this second meaning of discrimination that concerns human rights law.

How disability works?

Many people see disability as a condition that is inherent in the person. For example, a medical condition that forces a person to use a wheelchair or take medicine. However, the modern definition of disability sees disability as a combination of a person's personal condition (like being in a wheelchair or having trouble seeing) and environmental factors (like negative attitudes or buildings that are hard to get into), which together cause disability and limit a person's ability to participate in society.

For example:

Being in a wheelchair (a personal factor) combined with living in a city with accessible buildings (an environmental factor) leads to participation in the community on the same terms as someone who is not in a wheelchair: there is little or no disability.

There is a disability if a person has an intellectual disability (a personal factor) and the community thinks that people with intellectual disabilities can't vote (a negative environmental factor). This makes the person socially isolated and denies them the right to vote.

Personal factors are multilayered and can be both physical and socioeconomic.

For example:

Physical factors: gender, ethnicity, impairment (physical, visual, hearing, intellectual, mental), size and weight, and so on;

Socioeconomic factors: wealth, class, social inclusion, education level, and so on. Personal factors can either aggravate or improve disability.

Personal factors can aggravate or alleviate disability. For example, a wealthy person with a physical disability might be able to go to college and get a job that way. This might increase participation in society and alleviate disability to some extent.

Environmental factors can be associated with at least four sub-factors, which are as follows:

Accessibility: hilly or flat cities, accessibility of buildings (ramps, toilets, braille signs etc.), accessible information (websites, documents in easy-to-read formats), accessible public transport, etc.

Legal/policy: the existence of protection from discrimination compared with denial of rights based on disability, pro-poor policies, policies that refer explicitly to disability rights compared to policies that ignore persons with disabilities, etc.

Socioeconomic: rural/urban (present different accessibility issues), rich or poor, positive community awareness of disability, the openness of society to change, etc.

Services: inclusive services or segregated services (health, education, youth centres), community-based rehabilitation (CBR) services, social support services, affordability of services, etc.

The environment can either aggravate or improve disability. As disability awareness grows, positive and negative environmental factors often coexist. An accessible school might have ramps. Public transport isn't accessible, so a child with a physical disability can't attend school despite the open environment.

All of these things together determine how much a person can participate in society and, as a result, how much disability there is.

Different approaches to disability

Different approaches to disability exist in the world, some being more dominant in some parts of the world than in others.

The charity approach

The charity approach sees people with disabilities as passive recipients of charity or welfare payments, not as independent people with the right to participate in political, cultural, and personal development. This approach is different because disabled people aren't thought to be self-sufficient. Society supports them. This approach ignores environmental factors; disability is an individual issue. Disabled people are pitied and rely on society's goodwill. People with disabilities rely on charity houses, homes, foundations, and churches, to whom the community has given disability and responsibility policies. People with disabilities have little or no control over their lives under this model. They're a social burden. Because charity comes from goodwill, "care" isn't always consistent or significant.

If society’s responses to disability are limited to providing care and assistance for people with disabilities through charity and welfare programmes, opportunities for advancement are minimal. As with the medical approach, there is a chance that disabled people will stay outside of society. This approach does not support their participation.

If people with disabilities continue to be considered "unfortunate”, requiring compassion and depending on the contributions and assistance of others and on the goodwill of others, their opportunities for empowerment become very limited.

The charity approach makes it harder for people with disabilities to be equal and a part of society instead of making it easier.

The medical approach

The medical model emphasises a person's disability as the source of inequality. Medicine or rehabilitation determines a person's needs and rights to reintegrate into society. Medical treatment can help "bad" patients become "good," especially those with mental disabilities. Mentally disabled people are often feared. To be considered self-sufficient, a person with a disability must be "cured" or at least lessened. This approach ignores environmental conditions; disability is an individual issue. Disabled people are sick and must be fixed. Seeing disability as a medical issue gives doctors, psychiatrists, and nurses a lot of power over disabled people. The institution's staff makes patient decisions. Medical professionals consider patients' wishes. If disabled people can't get better, they'll stay in institutions. Successes and failures will be understood because of the person's disability. This can legitimise exploitation, violence, and abuse in the worst cases.

This model is combined with charity. Charities fund and operate rehab centres. This model's duty-bearers are the medical industry and government. Charity houses, homes, foundations, and religious institutions play a role when combined with charity. People with disabilities have little or no control over their lives under this model. The medical industry, professionals, and charities represent disabled people because they know what's best for their patients.

The social approach

The social approach recognises disability as the result of an individual's interaction with an unadaptive environment. This hinders the person's social participation. Disability doesn't cause inequality; society's failure to remove barriers does. This model puts the person, not their impairment, at the centre, recognising their rights as members of society.

Moving from a medical model to a social model doesn't make medical care, advice, and long-term help any less important. In the social model, they continue to go to hospitals and treatment centres for treatment. It responds to the patient's expectations, not the institution's. The social model recasts nurses, doctors, psychiatrists, and administrators. Dialogue will guide their interactions with disabled people. The doctor will be on the disabled patients' side, not on a pedestal. In the hospital, equality begins. The social model emphasises freedom, dignity, trust, evaluation, and self-evaluation.

In the social model, disability is part of society's diversity, not a "mistake." Disability is the result of personal and environmental factors interacting socially. Disability is a societal issue, not an individual one. Society should restructure policies, practices, attitudes, environmental accessibility, legal provisions, and political organisations to remove social and economic barriers to disabled people's full participation. It goes against charity and medical approaches because it wants disabled people to have a say in how policies and laws are made. The duty bearers are the state (all ministries and branches of government) and society. People with disabilities have the same rights as everyone else under this model. Disability is a burden on society, not on individuals.

The human rights approach

The human rights approach to disability recognises disabled people's rights and the state's responsibility to respect them. It says society's barriers are unfair and gives disabled people ways to complain. Take voting. Blind people can vote like everyone else. Blind people can't vote if the ballots aren't in Braille, and they can't bring a trusted person into the booth to help them. A human rights approach to disability recognises the lack of voting material and the inability to have assistance in voting as discriminatory and requires the state to remove such barriers. If not, the person can complain.

A rights-based approach to disability prioritises dignity and freedom over kindness. It tries to respect, support, and celebrate differences by giving people with disabilities meaningful ways to participate. It helps people with disabilities help themselves so they can participate in society, education, the workplace, political, and cultural life, and protect their rights by getting access to justice.

The human rights approach is an agreement between people with disabilities, states, and the international human rights system to use the social approach. All countries that signed the CRPD must use this method. States must end discrimination. The human rights approach says all policies and laws should be made with the help of people with disabilities. No "special" policies should be made for people with disabilities, even if they're needed to meet the full participation principle.

All state ministries and branches collaborated under this model. In this model, the state handled disability policies. Certain provisions involve the private sector and civil society, especially disabled people and their organisations. This model gives disabled people rights and tools to use them. They can control their lives and participate on equal terms. Under human rights law, disabled people must help make policy.

Which approach is dominant today?

The charity approach is the oldest of the four, followed by the medical approach. The social and human rights approaches are more recent. Even though the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities was passed, the charity and medical models are still common.

The consequences of the charity and medical approaches to disability

By approaching people with disabilities as “objects of pity” or “problems to be fixed", the burden of disability falls on the individual, and, as a result, social transformation is virtually impossible. Moreover, it can give rise to certain social norms that can make it even more difficult for people with disabilities to participate in society and enjoy their rights.

**The perception that people with disabilities are “special”

**

The difference between the medical or charity approach to disability and the social or human rights approach is how they treat people with disabilities. "Special" is often used to describe people with disabilities: special needs children, special schools, special services, and special institutions. The Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities avoids "speciality." Disability specialness may lead to marginalisation.

Special schools allow disabled people to interact with other disabled people or "professionals." This is unrealistic because it doesn't reflect society's diversity. Who benefits? Disabled? Disability-free? Separating humans seems counterproductive. Children should study and play together because they're social beings. Diversity must be the norm.

Segregated schools don't reflect society. Insufficient diversity. A disability-focused setting affects the problems "special" students and teachers discuss. When ideas and opinions clash, the audience lacks diversity, such as people without disabilities.

Education is a human right that affects others. Students with and without disabilities learn about society's expectations and opportunities. Theories, skills, and discipline are taught. They build on family and friendship values and create new ones. Children share timetables, venues, and responsibilities at school. Talking to teachers and other students helps students learn to live independently and with others. The school encourages early independence. This means having a job, participating in politics and public life, having a home and family, having access to justice, and having business opportunities. The diverse class makes it a great place to discuss human rights and different perspectives.

Institutionalisation is another way medical or charity approaches view disabled people as "special." People who are mentally, emotionally, or socially disabled are often put in psychiatric institutions against their will. They are taken away from their communities and can't choose their own medical treatments.

People with disabilities have the same freedom under human rights. Disability shouldn't limit someone's freedom. Disability-based institutionalisation is illegal. No one should be institutionalised against their will unless the reasons apply to others without disabilities (for example, imprisonment due to committing a crime and being sentenced by a judge).

People with disabilities can choose where and with whom to live in the community. Living independently isn't always done alone. People live in close quarters, sometimes in the same house. Families, friends, and colleagues live together. This is considered independent living.

When a person can make their own decisions, including where and with whom to live, they are living independently. Disability also applies. Independent living is supported. Disabled people can request support. Several human rights depend on being able to live on your own, such as the right to a decent place to live, the right to take part in public and political life, the right to privacy, the right to move around freely, and the right to vote.

**The perception that people with disabilities are dangerous

**

Mental and intellectual disabilities have historically been mistreated and neglected. They've been forced to get treatment, given electric and insulin shocks, and even experienced genocide during WWII. Some of their worst experiences were government-sponsored experiments on unknowing subjects.

Stigma and myths about mental illness continue to cause discrimination and exclusion. Stereotypes about people with mental or intellectual disabilities say that they are not smart, "weird," can't work, can't be helped, are dangerous, and can't be predicted.

News stories about violent acts or crimes done by "mentally ill offenders" have a big effect on readers. These stories reinforce the idea that people with mental illnesses are dangerous.

Such generalisations not only create a sense of risk, insecurity, and discomfort in society, but they also affect the self-perception of people with mental and intellectual disabilities. Low self-esteem fuels stigmas and myths. According to the World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry, "one of our greatest losses is our sense of who we are in our community." Forced treatment causes us to abandon our lives and return to a community that sees us as dangerous, volatile, and 'ill'

Mental and intellectual disabilities are powerless and poor due to discrimination. Due to the stigma surrounding mental illness, many disabled people are homeless, unemployed, undereducated, socially isolated, don't get enough health care, or are sedated and isolated.

Most people with mental and intellectual disabilities aren't violent and don't commit more violent crimes than others. Psychologically disabled people are intelligent and can function in many settings.

Saying that people with mental disabilities aren't more violent shows that violence is a social problem, not a mental one. It recognises environmental and social causes of mental illness, not just genetic and/or organic ones.

**The perception that people with disabilities are superhuman

**

The media portrays disabled people as superhumans. While trying to promote positive images of people with disabilities (which is welcome), the result can be one-dimensionality. They're brave, strong, and have overcome a disability. This positive image suggests most disabled people live hard, miserable lives. Disability is nearly insurmountable. The hero overcame many problems.

A disabled person has strengths and weaknesses, just like anyone else. Disabled people should be portrayed positively in the media. Art. 8 of the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities addresses this. This means bringing attention to disabled people who have done well in politics, sports, writing, or other areas. This person's only accomplishment shouldn't be overcoming a disability. The person has overcome academic excellence, coworker competition, community or family expectations, etc.

**The perception that people with disabilities are a burden

**

In contrast to the superhuman myth, society, family, and friends view disabled people as a burden. This is the opposite of the superhuman approach and is related to charity. The media perpetuate this misconception. How often have we seen a TV documentary about the struggles of parents of a disabled child, the attitudes toward their child, how their lives have changed, etc.? Focusing on the parents' struggles doesn't spread a negative myth about people with disabilities, but it has three immediate effects. First, the child with a disability's concerns, struggles, interests, and dreams become secondary. Second, the child appears flat, which is why her parents are upset. Third, the child seems trapped. Negative myths and stereotypes result.

This can have negative implications for people with disabilities. For example:

• They might believe that they are indeed a burden;

• They might come to expect that they are not meant to live independently;

• Parents and teachers may not expect them to be self-sufficient and accept responsibility for bearing the burden;

• People with disabilities, their parents, teachers, and other people who take care of them may add to the burden myth. On the surface, it seems like discrimination if an employer doesn't promote a disabled person because the disability will make the job difficult.

All of these can combine to prevent social change.

Forms of prohibited discrimination